Floating Point Numbers

Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee

Floating point numbers are such a common occurrence while programming that they're worth understanding at a fundamental level. Here I will go over what each of the bits of the float represent.

The IEEE-754 Standard defines the rules for how floating point numbers interact, but here I'd like to show some specific examples with a bit of math.

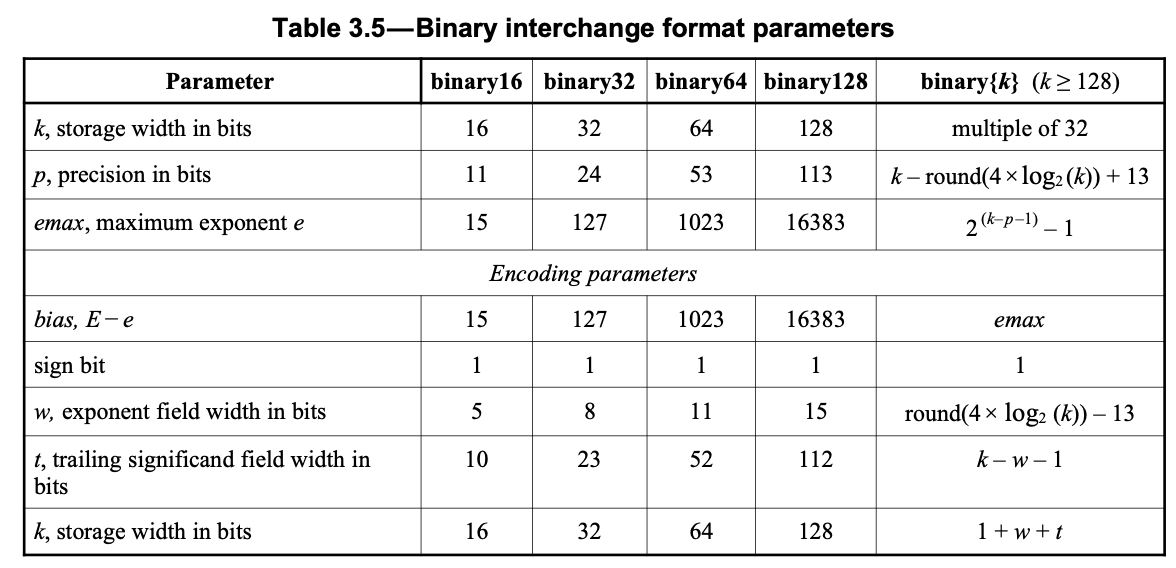

According to the standard, floats are made up of 16, 32, 64, or 128 bits.

There are a few constants defined by the standard which will come in handy later.

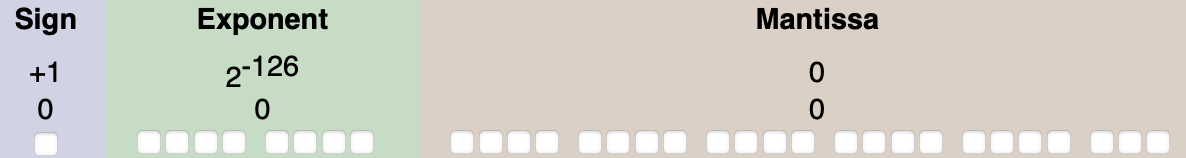

Here is the raw bit representation of a 32 bit float

Let's dig into what each group means!

Sign bit

This is probably the most obvious bit. It can either be 0 representing a positive number, or a 1 representing a negative one.

Exponent bits

From the table, these 5, 8, 11, or 15 bits (for 32, 64, 128 bit floats respectively) represent the biased exponent of the float.

We can break down the biased exponent into a set of bits () and compute its raw value:

Then the true unbiased exponent value can be computed by subtracting off the bias from the table (15, 127, 1023, or 16383), like this for 32 bits:

There are two special exponents:

- All bits are 0 - this represents a subnormal float, which we'll largely ignore

- All bits are 1 - this either represents a NaN or an inf (see special values)

Taking a 32 bit float for example, this gives us a range of

which is absolutely enormous! For floats that represent meters, this ranges from smaller than the planck length (~10^-35 meters) to much larger than the Milky Way Galaxy (~10^20 meters).

Mantissa bits

The exponent gives the floating point number its magnitude, but the mantissa gives the float its precision.

The remaining 10, 23, 52, or 112 bits are called the mantissa. The mantissa represents the fractional part of the float. We can likewise break this down into bits () and compute the mantissa value as:

You'll notice there isn't a bit for the 2^0 term, this is intentional. For normal floats, we can add on a 2^0 for free! This win is twofold: we get some extra precision without needing the extra space, and hardware implementations can specialize and assume a leading 1. Subnormal floats are a special case without the leading 1, but I'll ignore them here.

For 32 bit floats (including the leading 1), the mantissa can range between

Putting it all together

Combining terms from the previous sections, we can come up with the formula for a normal float:

Or with all the bit math removed

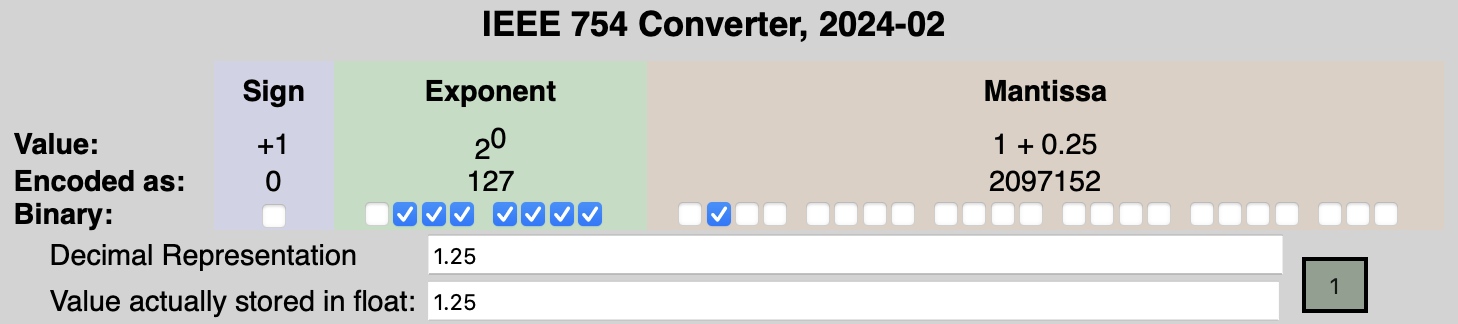

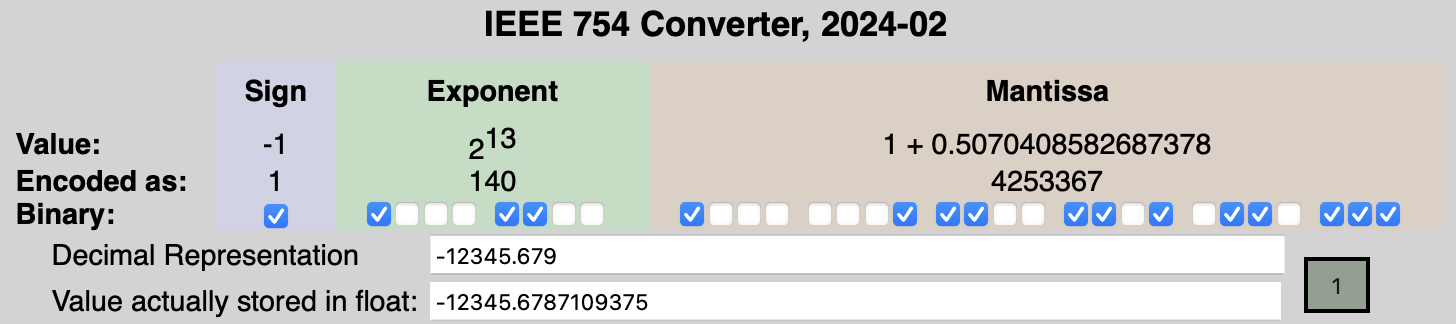

I'll be including screenshots for 32 bit floats from the IEEE-754 Floating Point calculator which is a really helpful tool to understand how they work in the wild...

1.25

| Bit Value | Actual Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sign | 0 |

1 |

| Exponent | 2^0 + 2^1 + ... 2^6 = 127 |

2^(127 - 127) = 2^0 = 1 |

| Mantissa | 2^-2 = 0.25 |

1.25 |

| Value | 1 * 2^(2^0 + ... - 127) * (1 + 0.25) |

1.25 |

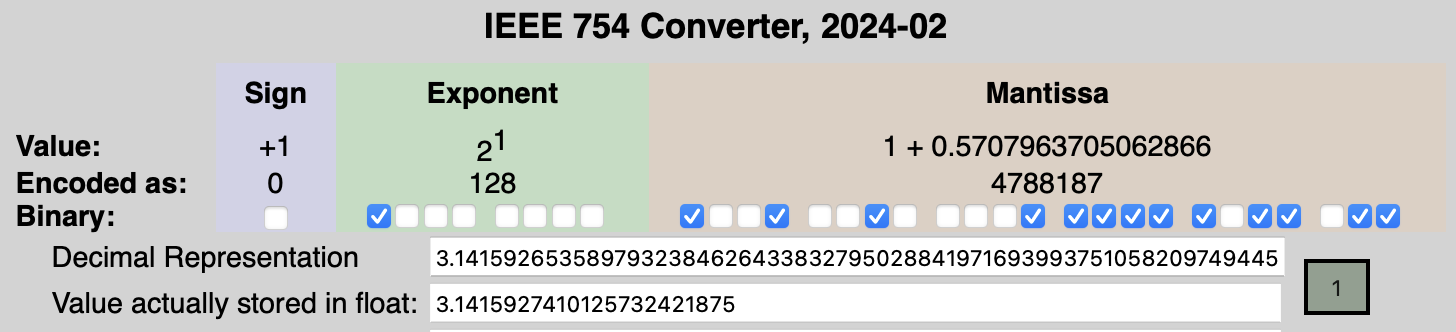

Pi

| Bit Value | Actual Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sign | 0 |

1 |

| Exponent | 2^7 = 128 |

2^(128 - 127) = 2^1 = 2 |

| Mantissa | 2^-1 + 2^-4 + ... + 2^-23 = 0.570... |

1.57... |

| Value | 1 * 2^(2^7 - 127) * (1 + 2^-1 + ... + 2^-23) |

3.1415... |

12345.6789

| Bit Value | Actual Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sign | 1 |

-1 |

| Exponent | 2^2 + 2^3 + 2^7 = 140 |

2^(140 - 127) = 2^13 = 8192 |

| Mantissa | 2^-1 + 2^-8 + ... + 2^-23 = 0.507... |

1.507... |

| Value | -1 * 2^(2^2 + ... - 127) * (1 + 2^-1 + ... + 2^-23) |

12345.6789 |

Caveats

It's important to keep in mind that floating point numbers arne't evenly spaced. At the lower end, adding 1.0 to the mantissa represents a step of ~2^-126, whereas at the upper end it is a massive ~2^127. This dramatic change can produce odd and surprising results when doing math on floating point numbers where precision in the operation is lost.

One place this comes up is when dealing with things like timestamps. If you count seconds with a 32 bit float, after counting for one day, the lowest step you can make is only 10 milliseconds.

Special values

Here is a table of the largest and smallest (normal) floats of the different sizes

| Min Value | Max Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Float16 | ~10^-5 | ~10^4 |

| Float32 | ~10^-38 | ~10^38 |

| Float64 | ~10^-308 | ~10^308 |

| Float128 | ~10^-4932 | ~10^4932 |

The standard defines a couple (really a few million) special values. As I alluded to earlier, when all bits are set in the exponent, the float represents either infinity, or NaN. These values can be "stumbled upon" when doing math - by dividing by zero, taking the square root of a negative number, or a handful of other dubious operations.

When the exponent has all bits set but none are set in the mantissa, the number is either positive or negative infinity. When any bits are set in the mantissa we have a NaN value. This gives 2^24 (2^23 mantissa * 2 sign bit) total NaN values - that's a lot of nothing!